I'm reading a novel called ‘The Seamstress’ by Maria Dueñas (original Spanish title 'El Tiempo entre Costuras'). It's a story about love, war, and espionage set in Spain and Morocco during the Spanish civil war and second world war. One of the characters, a young British woman named Rosalinda Fox, is described as having ‘a strange form of speaking in which words from different

languages leapt about chaotically in an extravagant and sometimes

incomprehensible torrent’ (page

193). I felt an immediate bond with Rosalinda because this is a perfect description of what happens to me when I 'mix up' foreign languages.

Background:

.jpg) |

| Building the Tower of Babel, Bedford Master, c.1410-1430 |

Because of this, I developed a theory that foreign languages must be stored in the same part of the brain (a different place from our mother tongue) and that they are layered one on top of another, with the most recently used on top. When the brain goes into 'foreign language mode', the neural channels that send messages from brain to mouth pass through that area, and whatever language is on the top is the one that's going to come out.

Language confusion:

So back to 2013: After spending January and February in Spain, my Spanish, albeit limited, felt comfortable and easily accessible.

|

| view of Alps on flight from Bilbao, Spain, to Munich, Germany, March 2013 |

My language mixing theory, updated for the computer age, now goes as follows: If we think of the brain as a computer, and languages as computer programs, then the program(s) for the language(s) we use every day are always running. They reside in RAM and there is no need to reload them every time we need them. However, languages that we don’t use are stored in long term memory, somewhere on the hard drive, and before we can use them, we have to retrieve them and load them into RAM. It wasn't that I didn't know the German words for ‘I’m sorry’ and ‘glasses.’ It was that I was trying to load a foreign language program into a place where another one was already running.

So how long does the loading process take? I guess it’s different for everyone, just as a computer program will load faster in a computer with more power. Age probably counts, as well as how much you've used the 'foreign language' part of your brain. Does it load in any particular order? Interestingly, what happened in my case was that the overall structure of the language loaded first, followed by specific words. As the hybrid sentence above illustrates, I experienced no overlap of grammatical structures, such as word order, between the two languages. It was only individual words that would 'jump' language boundaries. This suggests that the 'big picture' (the grammar) loads first, and that the 'details' (the words) come in more gradually, erratically, sometimes requiring great concentration, and sometimes falling easily into place. In an earlier blog post, Garmisch then and now, I described an occasion on the ski slopes when I saw a sign (for a ski run I used to go down), the sign triggered memories, and the memories activated language. I could almost feel brain neurons rearranging themselves as complete German sentences appeared in my head, like a blurry picture suddenly coming into focus.

There's an explanation for this in the literature. Michael Swan, in his article The influence of the mother tongue on second language vocabulary acquisition and use notes that we remember ‘fixed and semi-fixed expressions which are conventionally

associated with recurrent situations and meanings.’ Therefore, specific places and situations trigger the memory of the language that goes along with those places and situations. Even, apparently, after more than 30 years.

That night, in the hotel bar, 'it' happened again when I asked for ‘ein apfelstrudel, ein Glühwein, und ein wasser tambien’. (It's the words you don't think about, I told myself).

In the article mentioned above, Swan examines this phenomenon, which he calls ‘unintentional code-switching', and how it often affects the words you don't think about, the ones linguists call 'function' words.

Swan gives examples

of Finnish students learning English (their third language) who mistakenly used

Swedish (their second language) for words like ‘and’, ‘but’, and ‘though.’ Like me, the students knew the correct words, but, as Swan points out, 'knowledge and control are not the same thing.'

'Certain kinds of word may be more closely associated crosslinguistically than

others in bilingual storage or processing. In some second language learners,

for instance, function words such as conjunctions are particularly liable to

importation from the mother tongue and other languages.'

|

| where did that French word come from? |

A few days later I was back in Spain, and as expected, the German program lingered a couple of days in RAM before going back into long-term storage. My second day back, Corin started laughing at me in the supermarket; I had just asked the cashier for ein bolsa, bitte. One bag, please. (German in italics). For the first couple of days back, I had to stop and think about every single Spanish word, resulting in a strange, staccato form of speaking.

And so I was left to reflect on the mysteries of how we store, retrieve, and process languages. As a student and teacher of languages and language teaching, I wanted to know the science -- the cutting edge research from the field of neurolinguistics! But I didn't want to slog through pages of intimidating academic articles. I wanted to read something that gave funny examples and explained the key points in layman's terms. In the end, when I couldn't find an article like that, I decided to write one myself.

Anecdotal research:

First, I wanted to find other people who had experienced this type of erroneous language processing, and where better to look for corroborating evidence than the blogosphere? It turns out that there are plenty of examples. Below I've shared some of the best stories from my fellow bloggers, with links to their respective blogs.

Life in Ljubljana: Kristina Reardon, in her blog post Third language learning, relates her experience mixing up Spanish and Slovenian. She tells funny stories about 'my

brain’s inability to keep my Spanish and Slovenian separated in my head.’ She relates putting Spanish words into Slovenian sentences even though she knew perfectly well the

correct Slovenian word in each case. She describes how, when switching back to Spanish after learning Slovenian, there seemed to be 'a weight on my brain' and how she felt that Spanish was 'buried somewhere in my brain.'

Phrasemix: Then there’s Aaron, the guy who switches from French to

Japanese in mid-sentence. In his post Mixing up two foreign languages he describes his theory about why this happens: ‘It’s odd that I would think of the Japanese word instead

of the English, but I think that’s a product of how I mentally file my

languages. There’s a separate file for foreign languages that I search

in, and when I can’t find what I’m looking for in the French pile, I pick up

the closest thing I can find, which ends up being Japanese’.

Taken by the Wind: My next example is travel writer Reannon, who

writes a hilarious account of mixing up Spanish

and German called Do you ever mix up your second and third languages? She writes: 'My German hung awkwardly between me and the confused Mexican woman as I tried to think of a way to explain why a Germanic language had suddenly taken my Spanish language skills hostage'. She also describes having to resort to 'staccato' Spanish.

Kalinago English: My final example is Karenne Joy Sylvester, who describes her experience (also with Spanish and German) in Brains = filing cabinets or QuadPro hard drives? It's a short post, but the comments section has many more examples of others' experiences.

Academic research:

Next I looked for some 'proper' academic articles about what happens in the brain when we process language. My first question was where/how languages are stored, and my second was why/how they get mixed up.

I started with an article in the science section of the New York Times called When an adult adds a language it’s one brain, two systems. Sandra Blakeslee describes a study in which MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) was used to discover where in the brain

languages were stored. The subjects were

all bilingual; however, half of them had acquired two languages at the same time in childhood, while the other half had learned their second

language between the ages of 11 and 19. The question at hand was whether there were differences between the two groups regarding where they stored the different languages. Below is an excerpt, or you can click the link above to read the full article.

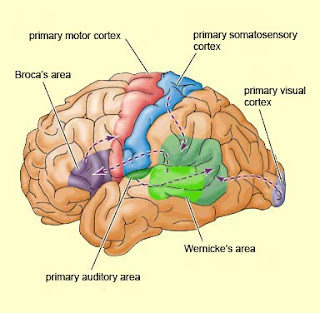

Aspects of language ability are distributed all over the brain, Dr. Hirsch said. But there are some high-level, executive regions that are usually localized in a certain neighborhood on the left side of the brain, but are sometimes found in the same neighborhood on the right side, or on both sides. One is Wernicke's area, a region devoted to understanding the meaning of words and the subject matter of spoken language, or semantics. Another is Broca's area, a region dedicated to the execution of speech as well as some deep grammatical aspects of language. The regions are identified by observing brain function.

None

of the 12 bilinguals had two separate Wernicke's areas, Dr. Hirsch said. In an

English and Spanish speaker, for instance, Spanish semantics blended with

English semantics in the same area. But there were dramatic differences in

Broca's areas, Dr. Hirsch said.

In

people who had learned both languages in infancy, there was only one uniform

Broca's region for both languages, a dot of tissue containing about 30,000

neurons. Among those who had learned a second language in adolescence, however,

Broca's area seemed to be divided into two distinct areas. Only one area was

activated for each language. These two areas lay close to each other but were

always separate, Dr. Hirsch said, and the second language area was always about

the same size as the first language area.

This

implies that the brain uses different strategies for learning languages,

depending on age, Dr. Hirsch said. A baby learns to talk using all faculties --

hearing, vision, touch and movement -- which may feed into hardwired circuits

like Broca's area. Once cells in this region become tuned to one or more

languages, they become fixed. If two languages are acquired at this time, they

become intermingled.

But

people who learn a second language in high school have to acquire new skills

for generating the complex speech sounds of the new tongue, which may explain

why a second language is harder to learn. Broca's area is already dedicated to

the native tongue and so an ancillary Broca's region is created. But Wernicke's

area, which handles the simpler semantic aspects of language, can overlap.

This is far from being the whole story, of course. Jennifer Wagner, Ph.D. student in

Languages and Linguistics at the University of South Australia, points to newer research such as this 2010 report suggesting 'nouns and verbs are stored in different parts of the brain,

similar to how our mental lexicon is further divided into phonological,

semantic and grammatical areas (for example, function words are only stored in

Broca's area.)'

|

| Noam Cbomsky |

For more fascinating facts about Wernicke's, Broca's, and other areas of the brain that are used in language acquisition, understanding, and production, check out Language in the Brain.

So far, then, the science seems to back up the anecdotal findings. Broca's area, where speech is processed, creates a separate space for languages learned after the age of first language acquisition. The 'language mixing' phenomenon seems to occur only when speaking, suggesting that it is processing and production, rather than knowledge, that is affected. Furthermore, Broca's area is where function words are stored, and it's the function words -- the ones you don't think about -- that are most affected.

B. Why do we mix our foreign languages?

Now back to the original question: The next two articles examine theories about why this phenomenon occurs.

(1) In Second language transfer during third language acquisition, Shirin Murphy

describes L2 (second language) interference in L3 (third language) 'often

without conscious awareness’, and how 'short L2 function words appear unintentionally

in an L3 utterance.'

Murphy points out that interference from L1 (first language) is rare, suggesting that the brain recognizes whether we are using our 'base' (native) language or what Murphy calls a 'guest' language. When in 'guest language' mode, we may experience 'failure to inhibit a previously learned second language adequately,' resulting in two of the 'guest' languages getting mixed up. Level of activation is another factor. At any given time, according to Murphy, different languages are at various stages of activation depending on proficiency and recent usage. A highly activated L2 (one that’s been recently used) is more likely to show up uninvited in L3 sentences.

Murphy points out that interference from L1 (first language) is rare, suggesting that the brain recognizes whether we are using our 'base' (native) language or what Murphy calls a 'guest' language. When in 'guest language' mode, we may experience 'failure to inhibit a previously learned second language adequately,' resulting in two of the 'guest' languages getting mixed up. Level of activation is another factor. At any given time, according to Murphy, different languages are at various stages of activation depending on proficiency and recent usage. A highly activated L2 (one that’s been recently used) is more likely to show up uninvited in L3 sentences.

(2) The last article I read was Faulty language selection in polyglots (no link; not available electronically). Benny Shannon first explains how what he calls ‘faulty interlingual

selection’ is different from 'code-switching', as follows:

Whereas Murphy described languages as being 'base' (native) or 'guest' (foreign), Shannon, divides language status into three categories: dominant (native), foreign (fluent but not native), and weak (in the process of being acquired). He presents the hypothesis of 'the last language effect,' where the ‘intruding language’ is more likely to be the last language acquired and/or used. Shannon

suggests that this happens because the weak languages are stored

in a ‘push button stack’ in our brains.

If this is the case, and if there is more than one weak language (i.e. two or more languages still in the process of being acquired) then there are two or more competing lexical items in each slot. Attempting spontaneous production of language (i.e. speaking) in this situation must be like a computer struggling to run too many programs at the same time and making that dreadful grinding noise -- or worse, locking up....

‘Whereas code-switching may be likened to the

(planned or spontaneous) joint employment of two (or even more) instruments

(e.g. musical instruments) that are at one’s disposal, faulty interlingual

selection may be likened to the faulty, unintended employment of one instrument

instead of another.’

‘Of special significance in this stack is the

terminal position, that occupied by the last language the speaker studied or

acquired (typically, this language is also the polyglot’s weakest

language). This terminal position is

constituted by slots assigned to lexical items which have not yet been

assimilated into one’s general conceptual database. Whenever a new language is acquired, new

values are assigned to these slots. As long

as the language has not been mastered, or as long as another language has not

been acquired, the lexical items of this language occupy the slots in

question.’

If this is the case, and if there is more than one weak language (i.e. two or more languages still in the process of being acquired) then there are two or more competing lexical items in each slot. Attempting spontaneous production of language (i.e. speaking) in this situation must be like a computer struggling to run too many programs at the same time and making that dreadful grinding noise -- or worse, locking up....

Conclusion:

|

| Tower of Babel; Pieter Bruegel the elder, c. 1563 |

Which brings me to those people who are able to switch between several languages simultaneously and easily. How do they do it? It's probably a combination of brain structure and constant practice. An integrated Broca's region means they are not running all their different languages as separate programs. Without that anatomical advantage, the next best option is to keep all languages activated by speaking (not just reading and writing) in them regularly.

As it happens, even computers and their complex advertising algorithms are not immune to language confusion. It's been two months since I came back to Spain from Germany, but Facebook is still sending me ads for 'Spanisch, ganz einfach!'

Bibliography:

The Seamstress,

Maria Dueñas, Penguin, London, (2009)

Swan, Michael: The influence of the mother tongue on second language vocabulary acquisition and use; ELT applied linguistics (2008)

Kalinago English, Brains = filing cabinets or QuadPro hard drives?

Phrasemix.com: Mixing up two foreign languages

Taken by the wind: Do you ever mix up your second and third languages?

Blakeslee, Sandra: When an adult adds a language, it's one brain, two systems, New York Times (1997)

Ekiert, Monica: The bilingual brain, Working papers in TESOL and applied linguistics, Teacher's College, Columbia University; Volume 3, No 2, (2003)

Nouns and verbs are learned in different parts of the brain; Science Daily, (2010)

Tettamanti, M., Alkadhi, H., Moro, A., Perani, D., Kollias, S., and Weniger, D. (2002); Neural Correlates for the Acquisition of Natural Language Syndicates, NeuroImage 17, 700-709

Musso, M., Moro, A., Glauche, V., Rijntjes, M., Reichenbach, J., Büchel, C., and Weiller, C., (2003); Broca's Area and the Language Instinct, Nature Neuroscience 6, 774-781

Examining Chomsky's inborn universal grammar theory, Boundless.com

Language in the brain, Boundless.com

Nouns and verbs are learned in different parts of the brain; Science Daily, (2010)

Tettamanti, M., Alkadhi, H., Moro, A., Perani, D., Kollias, S., and Weniger, D. (2002); Neural Correlates for the Acquisition of Natural Language Syndicates, NeuroImage 17, 700-709

Musso, M., Moro, A., Glauche, V., Rijntjes, M., Reichenbach, J., Büchel, C., and Weiller, C., (2003); Broca's Area and the Language Instinct, Nature Neuroscience 6, 774-781

Examining Chomsky's inborn universal grammar theory, Boundless.com

Language in the brain, Boundless.com

Murphy, Shirin; Second language transfer during third language

acquisition, Working papers in TESOL and applied linguistics, Teacher's College, Columbia University; Volume 3, No 1, (2003)

Shannon, Benny; Faulty language selection in polyglots, Language and Cognitive Processes, Volume 6, Issue 4, (1991)